Lemoore Chamber of Commerce next 'Citizen of the Year' worked to improve access to higher education and create jobs

On January 17, Gornick will be installed as the next Lemoore Citizen of the Year at the 62nd Annual Lemoore Chamber of Commerce Gala to be held at the Tachi Palace Hotel & Casino. The Lemoore Chamber this year will also honor Surf Ranch as this year's Business of the Year and the NAS Lemoore Navy-Marine Corps Relief Society as the Organization of the Year. Tickets for the event are available at the Lemoore Chamber of Commerce located at 116 Fox Street.

The summer heat enveloping the agricultural flatlands of the San Joaquin Valley's heartland is a long way from the frozen landscapes and biting winds that whip across Lake Michigan and race through America’s “Windy City,” Chicago, the Midwest’s capitol and one of America’s passageways to the west, where pioneers once set forth seeking the promised land.

Chicago was the boyhood home of future college president Frank Gornick, a restless sort of young man who spent his youthful winters shoveling snow and Chicago-style deep-dish pizza in his free time. It was in his hometown where he grew up playing football, the game he loved, learning it well enough to earn shot at a scholarship and a college education.

.jpg)

The son of Francis P. Gornick, a Chicago businessman who ran his own company specializing in industrial supplies, and mother Raphine Rossi, was prepared to move on at the right time, to experience life, to leave behind that windy city on the shores of Lake Michigan and begin his lifelong journey to respectability. He was the first and only Gornick to leave his native Chicago.

He said goodbye to mom and dad, his four sisters and a younger brother and hit the road for Tucson, Arizona, where rattlesnakes lurked beneath sun-drenched desert boulders and the stately saguaro cactus dominated the colorful Sonoran Desert, a stark contrast to midwestern Chicago where cacti and rattlesnakes are few and far between.

A youthful but energetic Gornick, who might have fancied himself a future NFL nose guard, tossed the snow shovel into Lake Michigan, and with the opportunity for a scholarship, soon found himself in Tucson, at the University of Arizona, where he played a year of freshman football (in those days, freshmen were not allowed to play varsity sports), but also where he quickly lost interest in that other important part of college life – the part that requires the occasional reading of a book. The scholarship he had earned when he made the team, was soon lost to his mediocre grades.

“I had a wonderful time,” said Gornick of his early foray into the world of higher education, “and that, was unfortunately a time that I did not distinguish myself academically.”

In time, he would remedy his youthful indiscretions.

In 1964, he was on top of the world – a talented athlete destined for good things – but a year later he was in Coalinga, about as far away from Chicago as one can get – and it was in Coalinga that things turned around for the young man from the Midwest. He learned about Coalinga Junior College from a University of Arizona recruit he was tasked with shepherding around the Wildcats’ campus. Gornick decided he was going to check out this California college in a place called Coalinga.

It was in this Westside community, once rich with the revenue abundant oil fields, that Gornick met his future wife, Gloria Garcia, the mother of their three children: Frank III, Victoria, and Christina. She was a local gal, a Lemoore High School class of 1964 graduate.

And it was in Coalinga that the affable Gornick earned the trust and respect of friends, coaches, and teachers at what was then referred to as Coalinga Junior College – long before it became West Hills College, the moniker it proudly bears today.

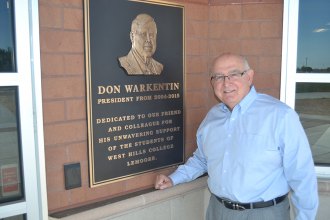

Yes, the future president and chancellor of the West Hills Community College District, began his stellar educational career in Coalinga, and ironically ended his productive career at that same school, where he is often referred to, as the most productive college president ever.

“it was kind of like a fantasy place,” said Gornick of his initial foray into the San Joaquin Valley and isolated Coalinga with its small community college. “The first thing I did, I had my friends from Coalinga, who knew me (there were other kids from Chicago there at the time) picked me up in Fresno and drove me out to Five Points, and they played a joke on me. They said, ‘here’s the college.’”

They eventually got him to the right place, and Gornick, upon first look, was impressed. “What was neat about Coalinga was that here you had this beautiful, manicured little campus, and this probably means a lot more to a kid from Chicago than it does for a kid from California, but we decided to go swimming that Sunday afternoon in the pool – in February. I thought isn’t this crazy.”

Swimming outdoors in Chicago in February isn’t recommended by Midwesterners where temperatures often are below zero – unless of course you enjoy mingling with polar bears or enjoy scraping ice from your beard.

Up to that point, Gornick had never been to California, and did he think it represented what the rest of California looked like? “From a weather point of view, yeah,” said Gornick. “I thought, yeah, this is really kind of nice, and teachers were just great, and the coaches were obviously just as good, and (being there) really brought my life back together.”

But there were minor worries. He often fretted that if Coalinga didn’t work out that maybe he was destined to join the military, eventually returning to his roots in Chicago. “Maybe I was going to go back to Chicago and work in the steel mills and eventually retire.”

But it all worked out. Coalinga was manna from heaven for the native Chicagoan.

In 1967, after proving his mettle in Coalinga and playing a year of college football – he was named the team’s captain – Gornick enrolled at Sacramento State where he joined its football team while taking up a new sport: rugby, which he continued to play well after his college days. He distinguished himself in college, earning double degrees in physical education and history. He stayed to complete a master degree in vocational rehabilitative counseling.

Next, the well-educated Gornick began a journey that took him from California’s San Joaquin Valley to Maryland, where he took a job at Howard County Community College for a year before accepting a position in the Dallas Community College District in Texas, where he served as the Richland College director of financial aid – from 1972-75.

Along the way, he earned a doctorate at St. Louis University.

He helped to start a college center in Bellville, Illinois and ran it until deciding that he and Gloria wanted to return to California. “We decided to go west,” said Gornick who accepted a job at Bakersfield College, where he remained until 1994, which proved to be a pivotal year for Gornick and the future of West Hills Community College.

Gornick, the Bakersfield College Dean of Students at the time, was happy with his job, but the lure of a college presidency beckoned. He applied four or five times at various schools but never made the final cut. In 1994, urged on by a mentor, Gornick reluctantly decided to apply for the president’s job at West Hills College.

And as 2017 there are many people glad that he did.

“The reason I applied was that I had a mentor by the name of John Collins who told me this would be a great job for me. He said I had the qualities and experience to turn this place around,” remembered a reluctant Gornick, who at that time was a bit wary of taking another stab at a college presidency.

“That was a bit hard for me to swallow. I thought I had a dream job in Bakersfield, and you know I was dean of students … the kids were doing great in school, all that jazz. But I had another friend of mine, who is currently president at Cuesta College (in San Luis Obispo) right now, and we were both deans of students at the time. He said I should apply.”

Gornick still resisted, asking his friend to give him one good reason why he should apply for the West Hills College job. “He said because you love your job in Bakersfield. That’s the best time to apply for a job, when you have no pressure, you just go ahead and tell them what you think.”

Gornick took his friend’s advice, applied and went through the interviewing process, culminating in a final interview scheduled at Harris Ranch. “I can remember that Gloria was driving the car on the way up, and the interview was at Harris Ranch. The night before I was working on some goals. My wife asked me what I was doing, and I said I was going to give the board a plan. She asked if I was sure I wanted to do that.”

Gornick told his wife that he had interviewed four or five times before, and the old approach didn’t net him that coveted president’s job. “The old approach didn’t work so I’m going to try a new approach,” he told her. “I based the plan on what I had observed, and what I observed was that there was great potential for growth in both Lemoore and Coalinga. There was great support for the college in both areas as demonstrated by what the city had done in Lemoore and what the city was willing to do in Coalinga…so I did my homework, and I saw that we were sorely lacking in outreach (to students), so I laid out a plan in terms of a five-year plan. Part of that plan, I told the board, was going to take the board to step up and say, ‘we’re going to need some more revenue from the taxpayers to make things happen.’”

Gornick, that once young man from Chicago, who went to college to play football, and found a measure of success in higher education, certainly made an impact on the West Hills College Board of Trustees during that job interview. His well-founded arguments got him the job he wanted, and he immediately set about bringing his vision to reality. But West Hills remarkable resurgence certainly didn’t happen overnight. It took lots of work and an innate ability to convince the district’s residents to join him in his vision.

Setting the stage for growth

Edna Ivans, 89, is the dame of California’s community colleges. The stately, soft-spoken Ivans, who could easily have been anybody’s favorite grandmother, is an anomaly in the world of elective politics. For 48 of her 89 years, the gentle lady from Avenal sat on the West Hills College Board of Trustees, her unparalleled tenure a California record for a school trustee.

She and her late husband, the Avenal pharmacist Nick Ivans, were pillars of their community – and big supporters of the local college. They were undying proponents of bringing to their small, isolated community in the foothills of the western San Joaquin Valley more jobs, a sense of community, and of course, an improved access to higher education, something both truly believed in.

The duo arrived in Avenal in October 1950, just barely out of college, and together they bought Tomer Drug with no money down – a good thing because the two incoming entrepreneurs didn’t have any.

Ivans believes that Gornick, whom she helped to hire in 1994, has made her dream of a vibrant West Hills come true.

“He’s done so much that it’s just been amazing,” said the personable Ivans. “He’s (Gornick) just done so much that it’s amazing. Each one of us sees what’s happened here – in Lemoore, in Avenal, and in Firebaugh. They just don’t realize the effect on the Valley and the whole state – what one person, with his leadership skills, has been able to do.”

Ivans is unabashed in her praise of the man she thinks turned West Hills around. She told The Leader that prior to Gornick’s arrival in 1994, the state of West Hills College was on shaky ground. The district consisted of The main campus in Coalinga and a simple one-building campus in Lemoore at the corner of Cinnamon and 19th avenues.

Since 1994, student enrollment across the district has almost doubled from 5,150 students to 10,252 today, thanks in part to Gornick’s vision and his ability to convince others of West Hills College’s bright future.

In those days, before the expansion of West Hills College in Lemoore and the rehabilitation of Coalinga’s campus, a high school counselor might ask a local high school senior – from Lemoore or Hanford – where she or he attended to attend college. The answer? Rarely was West Hills in the mix. College of the Sequoias, or Fresno City College, regularly topped the list. Rarely was West Hills considered by high school seniors, and even in hometown Lemoore, students, when asked where they planned to attend college, rarely mentioned West Hills College, easily dismissing the thought.

“Times were tight,” remembered Ivans. “Proposition 13 had been passed (1978) and at that time, West Hills, along with the other schools, we depended on that oil money. We had great schools (then). All of a sudden, our money was gone and it left us in a lurch. Things really got bad.”

In 1994, when Gornick came on board, West Hills was hanging on by the “skin of our teeth,” she recalled. “Getting center status was a big thing for us because (West Hills College) was all the people in Coalinga had. If they didn’t have the campus they wouldn’t have anything.”

It was a few years earlier – in 1991 – prior to Gornick’s arrival, that the foundation for growth was established when a hearty band of supporters, who believed in West Hills’ potential for growth, including then Lemoore Mayor John Luis and one other councilmember, joined West Hills President Stan Arterberry, Lemoore Center Director Don Warkentin, and the board’s Jeff Levinson, boarded a Sacramento-bound Amtrak train to bring an emotional but logical plea before the California Community College Board of Governors to grant Kings County Center Status to West Hills College.

The Governors agreed, effectively directing most state funding to West Hills College, rather than nearby College of the Sequoias as both aimed to expand into Kings County. With its small center in Lemoore, West Hills had already made the connection. College of the Sequoias was seeking a larger presence in Kings County but would have to pay for it with its own funds.

“Getting that center status was a big thing,” remembered Ivans, who attributes a lot of West Hills’ success to that decision. Gornick, once hired, capitalized on it.

The newly-minted president, in charge now of a fledgling community college, needed to act – and he was going to need help.

Building on the vision

To get things done, in a college district needing a healthy dose of adrenaline, required many things: competent marketing, a restructuring of class scheduling – guaranteeing students the classes they need to earn a degree – and outreach to the prospective students who, for so long, had opted to attend elsewhere when choosing a community college.

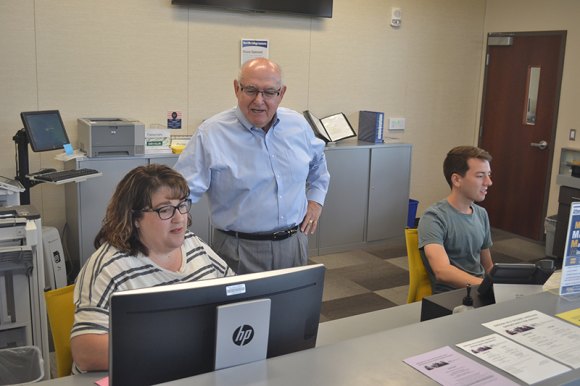

“We became much more effective in how we managed our classes,” said Gornick, reflecting on those first years. “And we became very focused on our outreach.” He and others visited local schools, talking with students, many of whom had long ago dismissed West Hills as a viable choice. Throw in a dash of effective marketing, and the West Hills College District began turning things around. But it wasn’t always easy.

Something had to happen in Lemoore. For years, the only visible presence here was a small non-descript learning center where students could enroll in a few classes. The small complex at the intersection of Cinnamon and 19th avenues was originally built in 1981 and was named the Kings County Center. But it didn’t offer many classes. Many students often had to make the drive to Coalinga, prompting some local students to opt for Visalia’s College of the Sequoias or Fresno City College, which had more to offer.

But Gornick and the governing trustees knew more needed to happen. Armed with the prospect for additional state funding, thanks to Kings County Center status, West Hills decided to go to the public in their effort to expand in Lemoore and to help provide the matching funds needed to expand its educational base.

But first, they needed to find a place to build a new Lemoore campus, and thanks to a pair of local farming families, Bill Pedersen and Lionel and Mardell Simas, West Hills found a new home. The families donated 107 acres to the West Hills cause, giving Gornick and the district an important tool with which to create new educational opportunities.

“Community colleges are all about location,” said Gornick, who liked the west side thanks to its proximity to highways 198 and 41. It seemed an ideal location to build a new college, and thanks to the generosity of the Pedersen and Simas families, it was going to happen.

“If you look at some of the older community colleges they’re embedded into the city in many places, so fast forward 50 years and you have parking problems, you have relationship problems with neighbors, you know all those kinds of things.”

Originally, Gornick asked about land north of Lemoore, which was better for the college. However, the local farming family said the requested property was good agricultural land, and they suggested the college think about the property they owned west of Lemoore, across Highway 41, which wasn’t as profitable or productive.

The families indeed donated the 107 acres in 1998 and West Hills College accepted, but there was still more work to be done, and the next step involved the taxpayers of Kings and Fresno Counties who needed to step up – and they did.

In 1998 local voters passed Measure G, a $19.5 million bond measure to provide funding for a new Lemoore campus and remodeling of the Coalinga and Firebaugh campuses, and thanks to local voters and state funding, West Hills College Lemoore opened for business in 2002, becoming the state’s 109th community college.

Local voters continued to support the district by passing Measure C in 2008, providing resources for Coalinga’s Farm of the Future and the modernization of several Coalinga campus buildings. Voters also passed Measure E, which provided $31 million for new buildings including the Golden Eagle Arena and the new 23,000-square foot Student Center that opened earlier this year.

More bond measures, an $11.8 million measure passed in 2008 helped fund Firebaugh improvements, and in 2014 local voters approved Measure T, a $20 million bond for technology upgrades for the next 20 years.

West Hills College Trustee Jeff Levinson, a longtime member of the Board, is pleased with West Hills College’s growth and gives much of the credit for the district’s national and statewide reputation to Gornick. “I feel very good about Frank’s 24 years as president of West Hills College,” he said. “Frank ran us right to the finish line. He brought a vision, and the vision was the endless pursuit of student excellence. He brought us a plan and he executed the vision.”

Levinson went on to say that the West Hills College District is a leader in the state community college system, adding that the West Hills College District is producing smart students, equipping them with the tools needed to compete in an ever-changing workforce.

“West Hills College produces smart employees ready to go to work to benefit cities like Lemoore, Coalinga, Avenal, Firebaugh, and elsewhere,” said Levinson. “We are (producing) prospective employees who can help local businesses.”

Gornick has done his job well, introducing innovative programs and earning the district rave reviews in national and state circles. Take for example its cutting edge Reg365, a student registration program that allows students to register for a full year of classes at once. West Hills also made developing open educational resources and free textbooks a priority, a goal that continues to be a focus today.

The district has indeed gained a statewide reputation for innovation and has been singled out for its dedication to innovation three times since 2015 by the state of California, earning three Awards for Innovation in Higher Education. West Hills was the only Central Valley institution honored all three times.

Community partnerships are the norm at the West Hills District. College graduates include nurses and psychiatric technicians who every year fill hospitals across the state. Intensive career technical education courses are being offered in everything from JAVA to HTML.

The list of innovations and partnerships continue.

Gornick and his wife Gloria plan to stay in Lemoore and they hope to continue assisting in the growth of the District. The District will be in good hands, said Gornick of Stu Van Horn, whose worked with Gornick for several years and was picked by trustees to take over as chancellor.

“People ask me about my leaving,” said the longtime college president. “I’m going to miss the people. There are just great people here, and I feel the district’s in great hands. I think Stu’s (Stu Van Horn) going to do an outstanding job. I’m okay with leaving now, and I think the board is on a great track.”Gornick also has a big thank you for the people of Lemoore, Coalinga, Avenal and elsewhere. “You’ve been great to me and my family. We have no plans to leave the area. We’ll still be around, and I’ll still be busy. Chancellor Van Horn said he may ask me to do a few things for him, and I’ll be more than happy to help him out. It’s been a great run, and there’s a lot more potential for this campus in Lemoore and I would encourage everybody to continue to support its efforts because it’s going to continue to pay dividends.”

Navy News

- For fourth year in a row, Stratford Elementary School welcomes Sandridge Partners who awards scholarships to 8th graders

- West Hills College Chancellor, Dr. Kristin Clark, announces her retirement, effective July 2024

- West Hills College officials host groundbreaking for new Lemoore Visual Arts and Applied Science Building in Lemoore

- West Hills College Lemoore to hold groundbreaking for new Visual Arts & Applied Sciences Building on December 1

- West Hills College Coalinga and Lemoore campus vie for 2025 Aspen Prize for college excellence

- Mary Immaculate Queen School's annual Fall Festival, held Sunday, Oct. 1, greets hundreds of local guests

_0.jpg)

.jpg)