Vietnam War's first and longest POW, Everett Alvarez, tells his compelling story to rapt audience while visiting NAS Lemoore

He was an elite Navy aviator – one of the country’s best – flying A-4 Skyhawk jets from the relatively new Naval Air Station Lemoore where the skies were open and the runways long.

He remains one of the iconic images of the ‘60s. Nestled amid student protests, rancorous politics, and of course the Vietnam War, Alvarez was an unfortunate symbol of that long-ago conflict.

While aboard the U.S.S. Constellation, cruising off the coast of North Vietnam, the U.S. Navy responded to the first shots fired during the “Gulf of Tonkin” incident, an episode that initiated the Vietnam War, the nation’s most prolonged conflict.

Responding to the historic Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 in the waters off Vietnam, then Lt. Alvarez, flanked by his A-4 Skyhawk compatriots – Lt. Cmdr. John L. Nicholson Jr. and Cmdr. Ronald V. Boch – flew one of the first missions from the decks of the USS Constellation.

In all, there were 10 Skyhawks assigned to mount an attack on the coastal target, Hon Gai, where the Vietnamese shipped out coal and where torpedo boats – alleged to have attacked the USS Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin – were moored. The Skyhawks all rendezvoused at 20,000 feet as they made their way to North Vietnam – and a date with war.

“Holy smokes,” I thought to myself. “This is war! We’re going into battle! My God! This could be the start of something really big!” Yet I wasn’t scared, just a little jittery. It reminded me of the butterflies I’d felt running track in high school, just before the starter’s gun went off.”

Excerpt from Chained Eagle: The Heroic Story of the First American Shot Down over North Vietnam

Alvarez was shot down as he and his fellow aviators mounted an attack on North Vietnam. He ejected just moments before his Skyhawk crashed into the sea. He was quickly apprehended and thus began his unfortunate journey as the longest-held prisoner of war in North Vietnam.

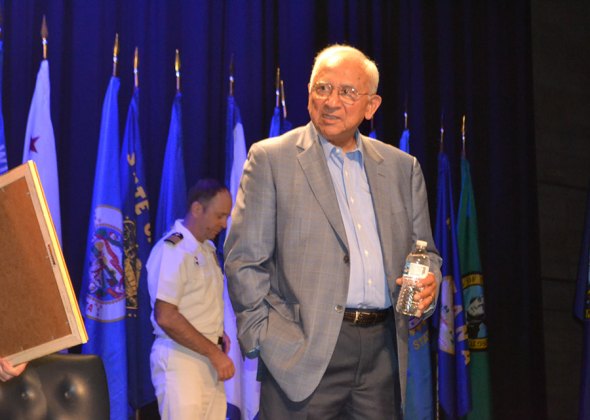

On Tuesday (Sept. 17) Alvarez returned to Naval Air Station Lemoore, joining his former Constellation aviators – Nicholson and Bock – on the Navy base’s theater stage where for well over an hour, the trio – the Navy’s version of a “Band of Brothers,” – sometimes delivered humorous, occasionally poignant recantations of the events from over a half-century ago.

The trio, introduced to a crowd of some 250-300 persons, didn’t disappoint, as both Nicholson and Bock, longtime career aviators, once stationed in Lemoore, delivered heartfelt remembrances of their captured comrade in arms, whom they lost one day over Vietnam and didn’t see for another eight years when Vietnam’s prisoners-of-war were safely returned to the United States.

Nicholson, who eventually retired as a Navy captain, was on that fateful flight on Aug. 5, 1964, when the enemy shot down Alvarez. He was the last person to have contact with his wingman that day. Nicholson is well known in the Central Valley, having served 20 years as Sanger High School’s NJROTC instructor. He currently lives in Santa Maria.

He grew emotional as he told his story, recalling his years in Lemoore watching his children grow up and attend the local schools.

Others recalled Alvarez’s return in 1973 when he reunited in Hawaii with his former commander, Nicholson. They saw each other, embraced and sobbed. Nicholson was the last American Alvarez had spoken to before his capture in 1964.

Alvarez took the microphone and calmly recited facts that he’s probably told hundreds of times to spellbound audiences, but the words remain powerful.

Standing on the staged with a microphone in hand, Alvarez told his story. “I appreciate being here today,” he said. “I’m overwhelmed, but I’m also reminded of the closeness and the camaraderie of the flight community,” he added, referring to the NAS Lemoore community. “I feel better about our country. You’re handling your jobs marvelously well.”

He remembered his initial foray into the San Joaquin Valley. “I remember driving here, and I was introduced to the Tule fog. I couldn’t find the base.”

He recalled that fateful day over North Vietnam as if it were just yesterday. “They saw us coming,” he remembered. “I fired everything I had. I used my guns because they were all I had left.

“We were passing over the southern edge of the town, approaching a hilly ridge overlooking the sea, when I heard a sound like “poom” following by a big yellow flash on the port (left) side of my windscreen. The plane shook violently, rattling and clanking as if someone had thrown a bucket of nuts and bolts into the engine. All my fire and hydraulic warning lights flashed on. Smoke filled the cockpit, the hydraulic system lost power, and the stick froze. Strangely, though everything appeared to be taking place in slow motion, it must have been my imagination, but I could not seem to move my hands, key the mike button, or even talk as fast as the crisis demanded.”

Excerpt from Chained Eagle

“I ejected because I was out of control.” He remembered the events as though they were just yesterday. “I found myself in the water. I was surrounded. In the distance, I saw some fishing boats.”

He saw rifles pointed in his direction. “I was scared. I was afraid they were going to kill me.”

Instead, he was picked up and taken into the nearby harbor. He didn’t have any significant injuries from his ejection, but he was ailing. “It hurt all over,” he recalled.

He spent about a week in the local jail before being transferred to the Hanoi Hilton, the prison that eventually held - according to U.S. Department of Defense lists – 687 U.S. POWs throughout the war. North Vietnam acknowledged that 55 American servicemen and seven civilians died in captivity.

“The stories (about the Hanoi Hilton) were horrible, and that’s true,” said Alvarez. It wasn’t until later that his captors began inflicting torture on him and other POWs. The North Vietnamese didn’t adhere to the Geneva Conventions, which governed the treatment of prisoners of war. “They let us know that we had no diplomatic relations with North Vietnam,” recalled Alvarez. “They let us know we were to be treated as criminals.”

To avoid revealing any pertinent information that may have assisted his enemies, he tended to “make stuff up.” For example, he told his captors that as an officer aboard ship, he was in charge of the popcorn machine. “We spent hours talking about popcorn,” he recalled.

His captors promised freedom if he apologized for his action or wrote a letter to Ho Chi Ming, North Vietnam’s leader at the time.

He did neither. “It was a bleak Christmas that year.” Early in 1965 he recalled hearing about another POW in the camp. More POWs arrived later, and in late 1965 his captors began their systematic torturing of their prisoners. “It was pretty brutal,” he recalled without going into specifics.

It wasn’t until late 1969 that the North Vietnamese changed their ways and the brutality lessoned.

A sense of camaraderie helped keep the prisoners hopeful. “We kept each other going. Spirituality played a big part.” While there wasn’t any church in the Hanoi Hilton, they did pray. “We all stood and said, ‘The Lord’s Prayer.’ We put our hands over our hearts and said the Pledge of Allegiance.”

While the captivity continued until 1973, most of the prisoners retained their sense of loyalty to America. “We had a code,” remembered Alvarez. “Return with honor – and we did.”

Since his release, Alvarez has led a productive life. He remained in the Navy, and after hospitalization, he briefly attended flight training with VT-21 at NAS Kingsville before attending the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School where he earned a master’s degree. His final assignment was in program management at the Naval Air Systems Command in Washington D.C. He retired from the Navy on June 30, 1980.

He also earned a law degree, and in 1981 President Ronald Reagan appointed the former POW to the post of deputy director of the Peace Corps. In 1982 Reagan nominated – and the U.S. Senate confirmed – him as the deputy administrator of the Veterans Administration.

While serving on several national boards, in 2004 Alvarez founded Alvarez & Associates, an IT consulting firm based in Washington D.C.

He is the recipient of the Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, two Bronze Stars, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and two Purple Hearts.

Interested readers can purchase Alvarez’s books, Chained Eagle and Code of Conduct on Amazon.com.

Lemoore

- West Hills College Thanksgiving food distribution held Nov. 15

- Lemoore High School celebrates Homecoming night with annual selection of King and Queen

- Tachi Hotel Resort Casino hosts 21st Annual Santa Rosa Rancheria Pow Wow

- NAS Lemoore squadrons return home after a long seven-month deployment

- Naval Air Station Lemoore crowd welcomed Lt. Dan Band and Gary Sinise

- Concerned Island District citizens gather Wednesday to hear Kings River updates

_0.jpg)

.jpg)